A Grisly End: Captivity and Death

A young Olga had once expressed to a governess her happiness that she was living in an era when “people were good,” when “evil men” had been “put away.” The irony of that statement is chilling, for the final years of her life coincided with the dawn of one of the most frightful times in her nation’s – and the world’s – history.

In March 1917, Russia as the world had known it for centuries ceased to exist. On March 15, the guards protecting the royal family (sans Nicholas) left the Alexander Palace. That same day, Nicholas abdicated in favor of twelve-year-old Alexei, then his brother Michael, who immediately surrendered his claim to the throne. (At this news, Alexandra began to burn her diaries and all of her correspondence except to her husband.) On March 19, the former Tsar asked the provisional government for safe passage to England for himself and his family; three days later, British Prime Minister David Lloyd George granted them political asylum, but King George III, their cousin, refused their pleas. Nicholas returned to his family on March 22. The royal family was put under house arrest.

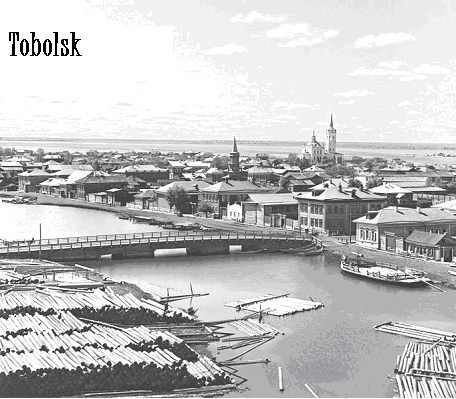

On August 14, 1917, the Romanovs were sent to Tobolsk, a Siberian town where Kerensky thought they could live somewhat comfortably. At this juncture, the underservants left the family, but tutors Pierre Gilliard and Sidney Gibbes faithfully went with the family to Siberia. Others accompanied them as well, including Nagorny the sailor. They lived in the white, two-story governor’s mansion, the finest house in the town. Kerensky sent Eugene Stepanovitch Kobylinsky, a colonel of the Petrograd Life Guards, to watch the royal prisoners; fortunately for the Romanovs, Kobylinsky was sympathetic to their plight. After a while, Vassili Pankratov took many of Kobylinsky’s powers, but even Pankratov was won over by the Romanovs. The family was at first allowed access to nearby buildings in Tobolsk, but their popularity with the locals led to the construction of a wooden fence around the house. Three hundred guards watched over the royal captives, yet some semblance of normal life continued, although visits to church were stopped in December. The girls continued their lessons; they sewed, embroidered, drew, read, and put on plays. In March 1918, Pankratov was dismissed, and the family was put on soldiers’ rations. All of the family’s remaining attendants, except for the doctors, were sent to live with them in the governor’s mansion, meaning people had to share rooms.

Nicholas, Alexandra, Marie, Dr. Botkin, and other servants were taken to Moscow (or so they thought). Secretly, Jacob Sverdlov, Lenin’s right-hand man, encouraged Bolshevik leaders in Ekaterinburg to seize the Romanovs, which they did. The family was installed in a cream-colored townhouse, known as the Ipatiev House and the disturbingly named “House of Special Purposes.” Back in Tobolsk, the others sewed their “medicine and candy” (code for jewels) into clothing, and a brute named Rodionov took over for Kobylinsky. But it was at the House of Special Purposes that things were truly horrible. The three girls and Alexei desperately wanted to reunite with their parents, and in late May, they, too, were sent to the Ipatiev House. Some of the household had been told those who went to Ekaterinburg would be put in the local jail. Many of the servants went anyway, and as foreigners, Gilliard and Gibbes were eventually freed. On the train, the girls, separated from everyone else, may have been raped.

By July 1918, the family had been ordered to be killed; this was known as the National Vengeance. Jacob Yurovsky was the new chief jailer. During the night of July 16-17, 1918, Yurovsky told Dr. Botkin that the family was going to be removed from Ekaterinburg because the White Army was nearing. Dr. Botkin went to wake them around midnight. The girls dressed in their jewel-laden clothes. Dr. Botkin, three servants, and the imperial family were all of the prisoners who remained in the house.

The Romanovs were ushered into the empty basement. Yurovsky and ten to twelve guards entered, and he announced the family’s fate. (It was payday, so the guards were drunk. Yurovsky had trouble finding guards to shoot the girls, and ultimately, half of those chosen for the grisly deed were Letts, Latvian mercenaries who wouldn’t have any ties to the Tsar’s family.) The Tsar was shot first; also in the first volley, the Tsarina was shot. (She died from being shot in the head, but the force of gunfire had literally knocked her out of her chair.) The guards’ orders were to shoot the children in the heart, but the jewels turned the girls’ corsets into bulletproof vests. The murderers then stabbed and beat the girls; all but Nicholas and Alexandra were still alive. Yurovsky shot Alexei at point-blank range. Marie and Anastasia were shot again. One of the servants was bayoneted and then beat with the butt of a rifle. After twenty or thirty minutes, there was stillness, so the bodies were put onto stretchers and thrown into a waiting truck. The girls were still alive; one sat up and cried out before again being savagely attacked.

It took three days to bury the bodies. Originally, the corpses were to be thrown into an abandoned mineshaft in the Koptyaki forest outside the city. The men tried to steal from the bodies, and they did not stop until threatened with death. When the townspeople found out about the “secret” grave, the bodies were removed from the mine to be taken farther into the woods to deeper mines. Instead, however, they were buried on top of each other in a three-foot deep grave near the edge of the forest; the faces had been maimed to prevent identification. The shallow grave was then doused with sulfuric acid to speed up the bodies’ decomposition. Alexei and Alexandra were supposed to be burned separately from the other bodies to confuse the White Army, but instead of Alexandra, the workers said they accidentally burned the corpse belonging to the lady-in-waiting. For seventy years, there the Romanovs and their loyal-to-the-end servants lay.

In the early 1920s, a young woman who would become known as Anna Anderson claimed to be Grand Duchess Anastasia. The first record of the woman was from February 17, 1920, when she was rescued from a canal in Berlin after a suicide attempt. For almost forty years, her case was in the West German court system; it ended in a tie in 1970. She maintained to her death at age 84 that she was Anastasia. Opinion is torn about the validity of her story, but hers was the most plausible of any of the claims to be one of the victims because she had the right type of scars and knew the right information.

In 1976, the secret grave was found; the following year, the House of Special Purposes was destroyed on Boris Yeltsin’s orders. It was not until 1989 that the whereabouts of the grave were made public, and when in 1991 the remains were exhumed, it was discovered that indeed two bodies were missing: Alexei’s and one of the Grand Duchesses’. In 1992, an American team was called in by the regional government to look at the skeletons. The Americans stated that if the remains were of the Romanovs, the missing Grand Duchess was Anastasia because the other skeletons were too tall and matured. The Russians were resentful, and a team of Russian scientists proclaimed that Marie’s body was missing. DNA tests proved the remains belonged to the Romanovs. They also showed that Anna Anderson was not Anastasia, but facial comparisons suggested she was, and the mystery remains.

Overall, seventeen Romanovs were murdered in the Revolution, but about twice as many escaped, such as Prince Felix Yussupov and Grand Duke Dmitri, both of whom had been banished for Rasputin’s death. Six thousand Russian aristocrats fled to Great Britain.

Further Resources

For more information about the Ipatiev House, go to: http://www.romanov-memorial.com/